An Act of Faith

|

| The Bear's Ears Monument. A testimony to Utah's unique place as a home for us in the past, present and future. |

The quote in the header of this blog was chosen based on

my deep belief that nature and wilderness are more than hobbies for me, they

are existential elements of my being. In light of recent events surrounding

southeastern Utah, the quote also holds some topical relevance. Another

treasured corner of my state has been designated as a National Monument and an

examination of why this is so

important to me and many others seems necessary as many on the opposing side,

some local, some national, question whether anyone in Utah wants this. My

answer is an emphatic, "YES!"

When I arrived in the west nearly 18 years ago, my scope

of wilderness was defined by very contrived experiences in confined spaces. I

may feel some kinship with nature in a state park carved out of the Door County

Peninsula, or I might feel a measure of vulnerability spending a few days

skiing in the savage winters along the shores of Lake Superior. That was my

experience with "wild" and "untamed".

|

| Idaho's Sawtooth Wilderness. |

|

| Enjoying happy hour in the legacy left by Frank Church. |

With my move to Utah just over 10 years ago, I joined a

new parish with different, but equally powerful examples of nature's glory.

While Idaho's vast central region was a blockade of mountains and rivers that

had been interrupting passage to the Pacific since Lewis and Clark, Utah

presented an inverse, but no less difficult geography. Deep meandering canyons

divide the Colorado Plateau's desert into large isolated chunks of desert.

Crossing to the other side of the Colorado River south of Moab requires long

pilgrimages to the remote missions in Hite or Bullfrog. And witnessing the

filigreed intricacy of The Wave just south of the border in Arizona demands

patience and dedication, not just in the procession through an unforgiving

desert on foot, but also in the faith that a permit to see this wonder would be

granted.

With President Obama's executive action to create the

Bear's Ears National Monument, another corner of our state has been sanctified.

In the eyes of us wilderness disciples, this decision validates our faith. Many

opponents question the designation. They feel it ignored the rights of those

who call the region containing Bear's Ears home. Certainly I can't pretend to call

Bear's Ears home, but do the residents of nearby Bluff and Blanding have any

more right to call it home?

I'll return to the quote at the top of this page. Yes,

nature is home-- our home. Snyder

didn't envision nature as parceled off plots for our personal refuge. There is

no boundary on nature where one person's opinion ceases to matter and another's

begins. Nature belongs to us all and it provides a home that stretches beyond

the Wasatch Front, Colorado Plateau, Intermountain West, Continental US and on

and on.

|

| The Wave exemplifies just how amazing a seemingly mundane desert can be. |

Many of us Altaholics get possessive of our

"home", so I can appreciate what some anti-monument activists feel.

But what matters most to me is that special places like Alta, Bear's Ears, or the

Jumbo Valley in British Columbia [watch Jumbo Wild on Netflix if you haven't]

are viewed not as local treasures, or regional treasures, or even national

treasures, but world treasures. That sentiment

understandably upsets those who see President Obama's choice as a threat to

their livelihood. Not only that, but I will recognize the action as a stinging

contradiction of their ideas of how nature should be managed, but using your

proximity to an area as an entitlement for environmental molestation seems self-centered.

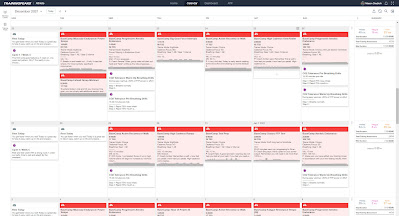

Introspectively, I have tried to find a point of

understanding, a parallel in my own life, that matches the anger fomenting from

the other side of the debate. I don't have to look very far. It's on the

calendar as January 20th.

That may seem drastic, but I have thought long and hard

about the compromises I might make for the preservation of the wild. For

example, would I trade Alta's snowboard ban for the preservation of Grizzly

Gulch and Flagstaff Mountain? Would I trade mountain biking in Fisher Creek to

ensure wilderness protections in the Sawtooth and White Cloud ranges of Idaho?

Who are any of us to say that responsibility towards

natures starts and stops on a property line. It surrounds us all. Gary Snyder

didn't want us to see nature as our home in the possessive sense. The

environment is not a plot in which we establish our dominion. He wants us to

see the entire system of nature as a gift that surrounds us every moment of our

life. We have all been given a home.

Comments